"a Simon Reynolds level culture blog" ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^"my brain thinks bloglike"

Saturday, July 26, 2008

Friday, July 25, 2008

A flurry of posts picking up on Sherburne's minimal/malaise article--Fisher@Mire on the genre's lack of fairground thrills; Hatherley focusing on the underlying class factor of Berlin as city of deracinated "creatives"; Fisher picking up on that to address minimal's lack of relation to a sense of place.

Nuum music is daubed and decorated with references to place, specifically London (just-4-U, sumting-dis, it's-a, etc) or specific areas of same (East, mostly), but these take the form of samples or track titles or other peripherals. On a sonic or rhythmic level I don't know if you can tie what's going on in jungle or 2step or grime or bassline to geography in quite the same way. The key factor is being tied to a population, a demographic cohort that keeps on renewing itself but retains a shared history and maintains a certain sociocultural consistency over a period of time, determined by factors of class and race. Vibe-tribalism. Not in a watertight, completely-closed off way, of course: there's an element to dance music tribalisms that is completely elective. Plenty of people became junglists or garagists by a willed act of allegiance (although it felt involuntary, like you'd been seized by the sounds). Through this violent cathexis they were jolted out of what might otherwise have been their "proper" place in the social cartography of music taste. The drugs certainly helped. But these new recruits, these immigrants as it were, from outside could only ever be a minority within the massive. Indeed when it reached the fatal tipping point, you got what happened when jungle became drum'n'bass; the genre was derailed from the Nuum-track when the original population was "swamped" by studenty types. With the vibe-defining majority, I think there's a real sense in which they are almost born into the tribe, through growing up surrounded by Nuum sounds, or (in the earliest days) with the music out of which the Nuum would form itself (sound system culture, Eighties pirate radio, Brit B-boyism etc).

If "population" is the key, then clearly the problem with Berlin specifically and minimal in general is cosmopolitanism itself. By definition, a cosmopolitan milieu is not going to be a fertile ground for tribalism.

Thinking about Gas recently I realised that tribalism in music is a form of quasi-nationalism (a tribe basically is a small nation), something that offers all the excitement of collective singlemindness and patriotic fervour with none of the suspect real-world aspects. It's an idea that rises to the surface of techno-rave's consciousness every so often, with slogans like "Rave Nation" or "Jungle Nation" or "Garage Nation". And as I've noted before, there was a time when I'd have happily put "junglist" on my passport.

What's the appeal of this pseudo-patriotism? Surely it has something to do with globalisation; with the deterritorialising effect of transnational capital; with the erosion of earlier forms of solidarity and collective purpose, e.g. trade unions; the longing for belonging. The music-based or subcultural forms of nationalism offer a softcore surrogate version of what political nationalism offers: identity, community, a sense of values that transcend those of the market. (Think of the role nationalisms of various sorts and extremes played for most of the 20th Century as a sort of "Neither Wall Street nor Red Square" Third Way). Being a genre patriot, a member of a vibe-tribe, asserts a relationship with music that goes beyond simply consuming it, beyond use value. Similarly, just as political nationalism asserts an organic community in order to seal over/magically heal/resoluve/suppress the reality of class divisions, music-tribalism achieves the same kind of effect through aesthetics.

Of course, confusing matters, techno culture has also indulged, especially in its early cyberdelic days, in the rhetorics of globality, border-crossing, world unity of dance, deterritorialisation, etc, very much in line with a Wired magazine type view of "progressive" capitalism. But the Nuum runs contrary to that, always has; it began as a reterritorialisation, an assertion of the local, the "UK" prefix. Perhaps (echo of Hobsbawm) the Nuum is a kind of invented tradition, a tradition that harks forward, to the future. (Actually, it is looking both ways at once--roots'n'future).

I wonder if there is also a question of time involved, a class-based relationship to the experiencing and management of time. Fisher, picking up on a point made by Sherburne, wonders whether the curious peaklessness of minimal (so similar to that other "global underground", Sasha/Digweed-style progressive) relates to "the libidinal cost of distending pleasure over the course of a twelve hour party." It's partly that, but also because the division between the ecstatically heightened timezone of "party" and normal existence is not as drastically demarcated.

"Creatives" have a different relationship to work and leisure than people who work in manufacturing or the service economy. There is a sense that they are rarely fully at work or fully at leisure. Because their jobs are more fulfilling, there is not the same sense of your-time-is-not-your-own, enforced boredom, nothing like the same alienation. The stress in this kind of work is often enjoyable stress: the challenges of solving problems, the adrenalin rush of the approaching deadline, the team-pulling-together-vibe at, say, a magazine when it's closing an issue and everyone's working until midnight. That kind of positive stress is virtually physiologically different to the cororonary-building kind of stress of being at the end of a supermarket or factory conveyor belt, subject to its rigid and inhuman flows (something I recall vividly from a summer spent as a student worker at the Wellcome plant in Berkhamsted, packing aerosols of insecticide into cardboard boxes). Also, if you work on a computer it's very easy to bunk off at frequent intervals, play truant into the web world, exactly as I am doing right now. At the same time, because their media or design jobs often involve aesthetics or some form of cultural information-gathering or semiotic interpretation, or networking, there is a sense that they are seldom completely at leisure. Work and leisure, the workspace and the homespace become blurred.* Especially if you are a freelancer and can manage your own time.

Because of all these factors, the whole explosive tension-release, living-for-the-weekend economy of energy that underpins the more tribal-vibal forms of dance culture is absent in minimal. It is much more about a plateau state of pleasure and pleasantness--the music coming through the speakers at the club not being that different from what you're playing all day through your computer speakers.

The weekend is not the redemption of a week of drudgery, because the work isn't actually drudgery, but stimulating. Because the weekend is not the focus to the same extent, there's no need to brock out, less pressure to release . The last time I was in Berlin, earlier this year, after the Rip it Up reading a bunch of us checked out some minimal bars, including one famous club, Watergate, with glass window walls overlooking the river. It was Wednesday and the place was pretty packed, full of people clearly there to dance until 6AM or later. On one level it was really cool to see people out and partying in the middle of week; on another there was that level, chugging thing to the music, the sense that there wasn't going to be a peak hour as such.

Finally, I wonder if some of this connects to issues addressed in this interesting post by Dan at The End Times. A fundamental transformation in the nature of bohemia. At one point living a bohemian life meant embracing failure, squandering the opportunities and privileges of your class background, a deliberate self-impoverishment that rejected the conventional ideas of wealth and success in favour of spiritual and aesthetic riches. Now certain aspects of bohemianism--a life dedicated to aestheticism, exquisite sensations, "experiences", the exotic; systematic derangement of the senses (albeit as brief forays rather than a permanent condition); an unstructured and de-routinized lifestyle--have become compatible with an essentially affluent and careerist existence.

* One interesting thing in Sarah Thornton's Bourdieu-esque book on dance music Club Cultures is that she notes the rigid divide maintained in 90s UK clubland between work and play, your real-world identity and the nightlife self. She claims that strangers fraternising at raves and club might talk about all kinds of things very candidly, but the one taboo was the question "what do you do for a living?". This probably mainly related to the founding myth of classlessness then still upheld in club/rave (despite the reality of its increasing fracturing into taste niches), a subconscious impulse to keep the real world of production and social divisions outside the club space. But still, I bet nothing like the same taboo maintains in the micro-minimal world. I'm sure it's totally acceptable to talk about your projects or profession in between bumps of K. Because the assumption is, everybody in the place is from the same kind of place, socially.

Thursday, July 24, 2008

Talking of Marxists feeling obliged to conceal their pop culture love behind aliases, Kirk Razga tells me that Eric Hobsbawm--regarded by some as our greatest living historian and a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain from the Thirties right up to just before the party dissolved in 1991--was a jazz critic for the New Statesman in the 1950s using the pseudonym Francis Newton, under which name he also published a book, The Jazz Scene.

Tuesday, July 22, 2008

talk of Perry Anderson (someone I've been investigating as a knock-on of re-grappling with the incomparable turgor of Fredric Jameson's Postmodernism - supposedly Anderson's The Origins of Postmodernity is a remarkable elucidation of Fred's work on pomo and its relationship with Late Capitalism) reminded me that recently I stumbled across, for the second time, an online deposit from Anderson's shortlived foray into rock criticism. This was in the New Left Review, at the cusp of the Sixties into Seventies, but using the pseudonym Richard Merton. And judging by this one piece, not bad at all: I particularly enjoyed the swipe at Dylan:

"Suffice it to say that Dylan’s undoubted historical importance should not be confused with his aesthetic claims. Within the metamorphoses of American rock, he plays something like the same role as Chateaubriand, fons et origo of European romantic literature in the last century: an omnipresent influence, monumentally reedy, vain and feeble in itself, yet paradoxically fecund and liberating for its successors, because of its impacts on genre, Dylan’s self-pitying verse and prophetic posturings again and again produce inferior art (sometimes nauseatingly so — items such as "Just Like a Woman" are a nadir by any criteria). Yet out of these vapourings have emerged groups like the Byrds and the Band."

Better than "not bad at all," though, is the fellow New Left Review contributor that Merton/Anderson is here arguing with, one Andrew Chester, who penned the initial piece, "For A Rock Aesthetic" (shades of Carducci, but from the opposing side of the political barricades), and who then returns to respond to Merton/Anderson's critique with "Second Thoughts on a Rock Aesthetic: The Band". Chester's opposition between "extensional" and "intensional" modes of development in music seems to have loads of applications, and indeed I applied this very dichotomy in a small way in one of the more theory-oriented chapters in Energy Flash, having first come across it cited and deployed in Simon Frith's Performing Rites. But whereas Merton/Anderson went on to become a major figure in modern Marxism, I can't find any clues online to indicate what Chester went on to do or be. (Unless this is the same chap, which there's no real reason to believe--plus a 37 year gap between publications seems unlikely). Anybody knows what happened to this guy? And is there a lot more decent rock writing tucked away in the NLR archives (Chester's piece alludes to an article on the Stones by Alan Beckett) or was it all just a brief infatuation?

Another question is why Perry Anderson felt obliged to adopt an alter-ego to do his rock writing. Was pop culture at that point still considered a bit infra-dig and insubstantial for yer proper Marxist scholar to be expending intellectual energy on?

superb, and strangely suspenseful, piece of writing from the Impostume that starts from the unlikely fact that thirteen years ago he lived in the same street as Chumbawamba....

Thursday, July 17, 2008

Philip Sherburne addresses the malaise in electronic dance culture (i didn't know the economic side of it had gotten that parlous)and convenes a kind of brain trust to come up with remedies

Friday, July 11, 2008

Monday, July 07, 2008

Ye olde skoole blogg action!!!

Fired up by funky house, Finney reactivates the thirty-months-dormant Skykicking!

That's for the trees-not-wood close analysis of hott trax.

The macro-view theory is deposited here.

"Funky house's combination reference points (tribal house, soca, the decidedly bourgeois "broken beat" scene) can seem rather staid on paper."

You can say that again! A triple-fold case of "vibe migration" that could only be more improbable if reggaeton was somehow involved as well.

But I shall reserve further judgement until I've checked out the Marcus Nasty dj sets Tim be raving about.

Thursday, July 03, 2008

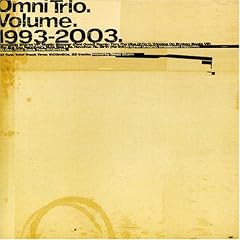

interview with Robert Haigh: Omni Trio, mission formally terminated; new recordings, solo piano, imminent. And who knew the basement of the Oxford Street Virgin megastore was such a hive of esoterrorist activity...

I didn't even know this came out!

Then again I made my own equivalent across two CD-R/80's, although the time-frame in my case was 1993 to 1996, "Mystic Stepper" to "Torn".

Weird to think Haigh probably recorded and released more Omni Trio material after Haunted Science than up to and including it...

One of these years I expect I'll get around to listening to those four post-Haunted albums...

I'm not a very good fan, basically. Even with my absolute all-time favourite musicians (among which company Haigh places high)that completist, stick-with-them-all-the-way-through impulse isn't really there...